New methods of fencing cattle on farms could improve farming outcomes and restore land and riparian areas. Virtual fencing is an electronic fencing system for cattle. It relies on GPS-defined boundaries to give cattle sensory cues that make the animal avoid a certain area.

Attaching a GPS cow collar. Photo credit: Agersens

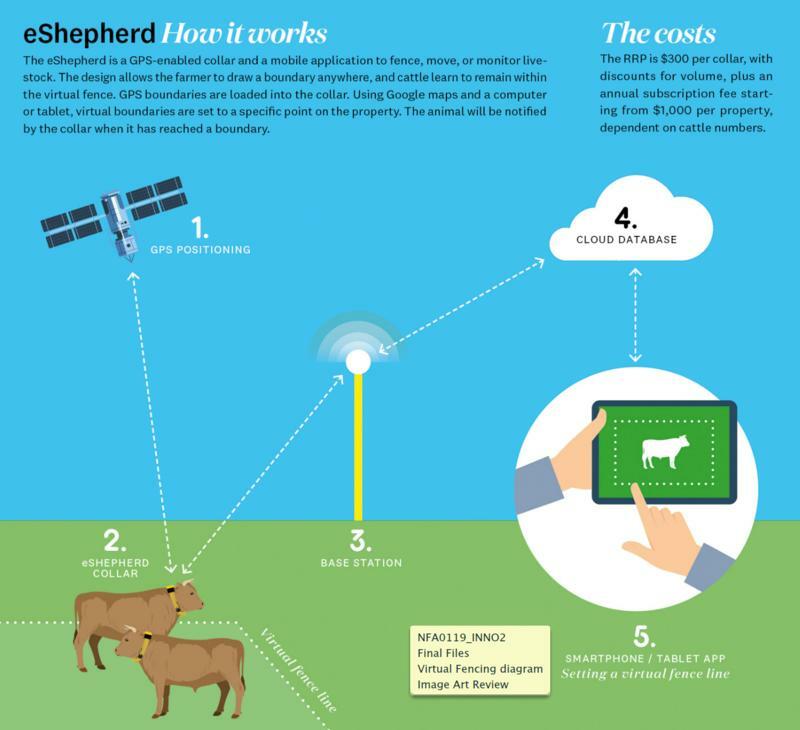

Melbourne-based company, Agersens, in conjunction with CSIRO have been trialling a commercial solar-powered virtual fencing project on farms around Australia. This technology reduces the resources required in regular fencing, and has ecological benefits for land on farms, and is now commercially available.

Jason Chaffey, chief executive of Agersens, explains that “when an animal approaches the border of the virtual paddock, the neckband will emit an audio warning, and if the animal continues towards the virtual fence, the neckband will produce a mild electrical pulse.”

Virtual fencing offers many benefits for both farmers and the environment:

- It significantly reduces the financial, social and ecological cost of regular stock fencing and herding. Virtual fencing retains the precision and effectiveness of regular fencing, whilst maintaining the flexibility of herding. It allows cattle to roam a paddock without completely ruining native vegetation areas.

- Predation and over-grazing along traditional fence edges are minimised by the flexibility of virtual fencing.

- Native species are able to cross the virtual fence, and maintain ecosystem connectivity.

Cows with GPS collars taking a keen interest in somebody’s hat!. Photo credit: NSW Farmers

There are, however, some drawbacks with the technology that are still being studied and addressed:

- Whilst physical fences can keep out unwanted pests or animals away from farming land and cattle, virtual fencing does not. It only prioritises keeping cattle from certain areas.

- Physical fences provide a reliable barrier to disease transmission between different animals or species, whereas virtual fencing cannot ensure this.

- Ethical considerations of giving animals electronic sensory cues are still a key concern. The main issue is that every individual animal reacts differently, and so what may be a completely normal level of shock to one animal, could be harmful to another. Another issue is that an animal may not sense the shock and continue to cross the virtual fence, so the collar could continue to shock the animal until it returns to the zone.

- According to the RSPCA, there is a lack of research regarding the long-term impacts of the technology on animal welfare. Furthermore, the lack of predictability from constantly changing the boundaries can cause stress and anxiety for the cattle.

Image credit: NSW Farmers

Virtual fencing is not a modern concept

Farmers have been experimenting with virtual fencing for as long as humans have been domesticating livestock and plants. A 2013 study by Jachowski, Millspaugh and Slotow (link below to full paper – Good virtual fences…), looked back on historical forms of virtual fencing. They defined virtual fencing as restriction or control of animal movement without the creation of physical barriers. Some examples included strategic placing of carnivore urine with high concentrations of sulfurous metabolites from meat digestion used to deter prey species, chemicals applied topically on plants or genetic manipulation to ward off herbivores. Visual and auditory frightening devices such as strobe flashing lights, flags or, for marine species, underwater acoustic alarms.

The study also looked at biological fencing, which is the intentional planting of species to control the movement of another species. For example, guard dogs have been used as roaming barriers to predators. Other biological virtual fencing examples include planting chili peppers in Zimbabwe to reduce the risk of wild animals passing through agricultural areas and causing damage, and bees, old hives or buzzing sounds have also been effective at limiting crop-raiding by unwanted wildlife.

A bee hive suspended in a tree to act as a deterrant to wildlife raiding crops. Photo credit: The Jiwa Damai Blog

The verdict

The potential environmental benefits of virtual fencing are significant, as it offers the opportunity to be able to protect vulnerable areas like streams, wetlands and native vegetation, within large properties that are unable to be fenced. Clearly, more research is necessary to address the ethical concerns of the collar technology, but it is worth noting that dog and cat ‘hidden’ fences have been available for many years and use a similar approach. Further testing of the cow collar continues in Victoria, South Australia, Western Australia, the Northern Territory and ACT. It is also being commercially trialled in Tasmania, New South Wales and Queensland.

Where to for more information?

- Virtual fencing – past, present and future (CSIRO)

- Huge strides for virtual fencing

- Virtual fencing technology for natural resource management

- CSIRO Virtual fencing

- Good virtual fences make good neighbors: opportunities for conservation

How to plan for success when managing riparian area

Taking a ‘whole farm approach’ is recommended when planning how to protect and restore healthy riparian areas. A whole farm plan will typically help you identify the different parts of your property, the connections between them, and their actual and potential contribution to your business. ‘Section 4’ of our Managing Stock and Waterways Guide explain what this approach typically involves.