“Most species of willow are Weeds of National Significance. They are among the worst weeds in Australia because of their invasiveness, potential for spread, and economic and environmental impacts. They have invaded riverbanks and wetlands in temperate Australia, occupying thousands of kilometres of streams and numerous wetland areas.

Unlike most other vegetation, willows spread their roots into the bed of a watercourse, slowing the flow of water and reducing aeration. They form thickets which divert water outside the main watercourse or channel, causing flooding and erosion where the creek banks are vulnerable. Willow leaves create a flush of organic matter when they drop in autumn, reducing water quality and available oxygen, and directly threatening aquatic plants and animals. This, together with the amount of water willows use, damages stream health.”

– Weeds of National Significance website

Willows love Australian rivers…

Willows do extremely well in Australian conditions, and have spread from people’s gardens out into our landscape, establishing along and within wetlands, streams and creeks in south eastern Australia, particularly in the Murray–Darling Basin. We also used to plant willows for bank stabilisation, but we have inadvertently created a problem with 30,000 km of the 68 000 km of river frontage in Victoria, now dominated by willows. A more recent estimate of the total area of riparian zone willows in Australia is 21 015 ha; 76% in Victoria and 16% in south-eastern New South Wales (Steel et al. 2008 cited by Doody et.al 2011).

Willow colonization causes environmental impacts on stream and wetland health. The trees have dense root systems that maximize water uptake and form thickets that allow trees to grow across stream beds, as the roots trap more and more sediment. Water movement is slowed and may be diverted around these dense thickets, causing stream bank erosion as water is diverted outside the natural stream channel. Willows are also hybridising, furthering their spread and colonising many large and small river reaches.

Most willows in Australia have been classified as Weeds of National Significance because of their extensive spread and threats to stream ecology and flow. It is illegal to sell or plant willows in Australia, with the exception of Salix babylonica (Weeping Willow), Salix calodendron and Salix richardii (both sub-species of Pussy Willow).

Willows, if left unchecked, choking a stretch of river. Photo credit: Antia Brademann.

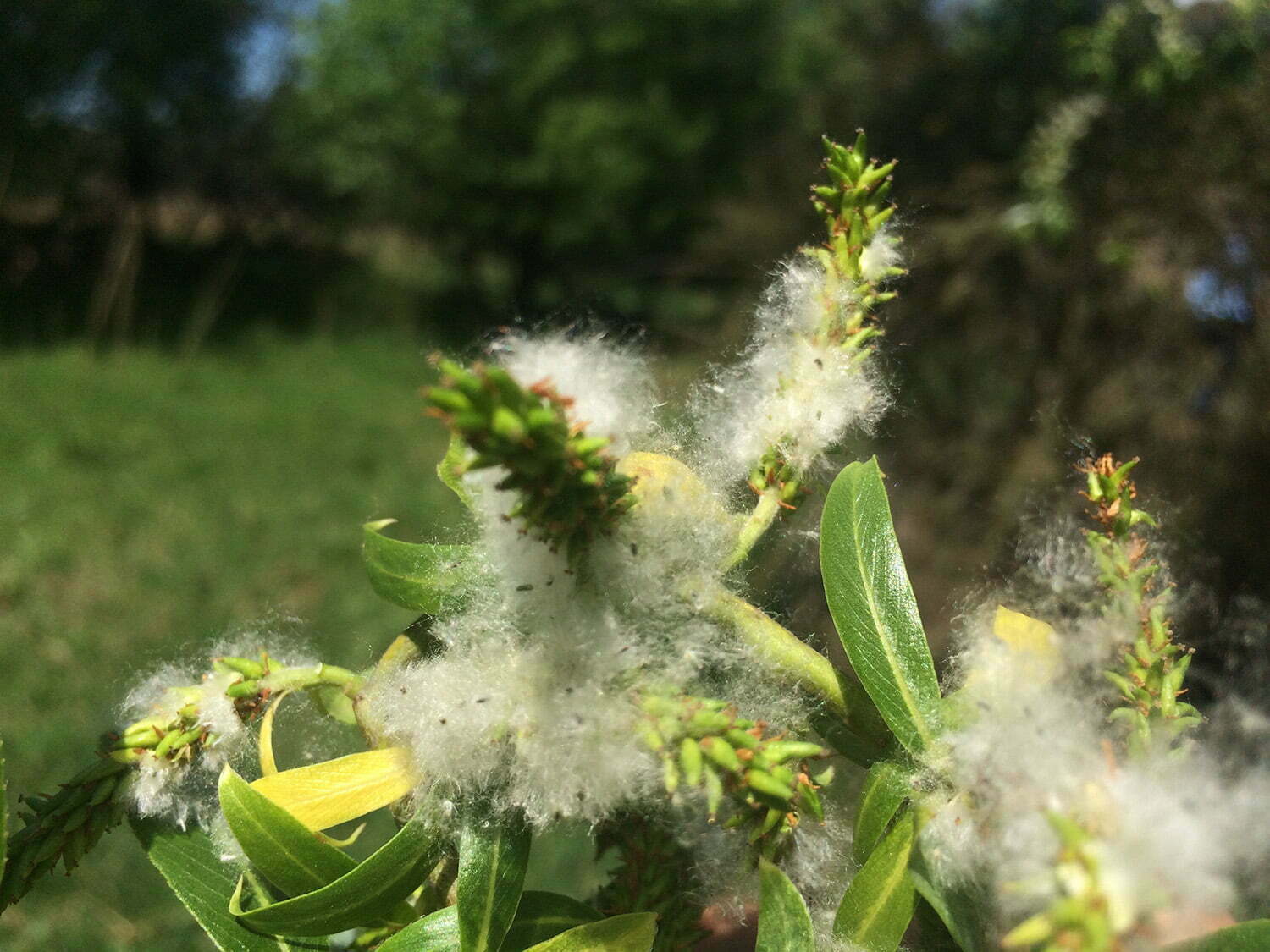

Willows blossoming, seeds spread widely. Photo credit: Antia Brademann.

Willows reduce water quality and instream health

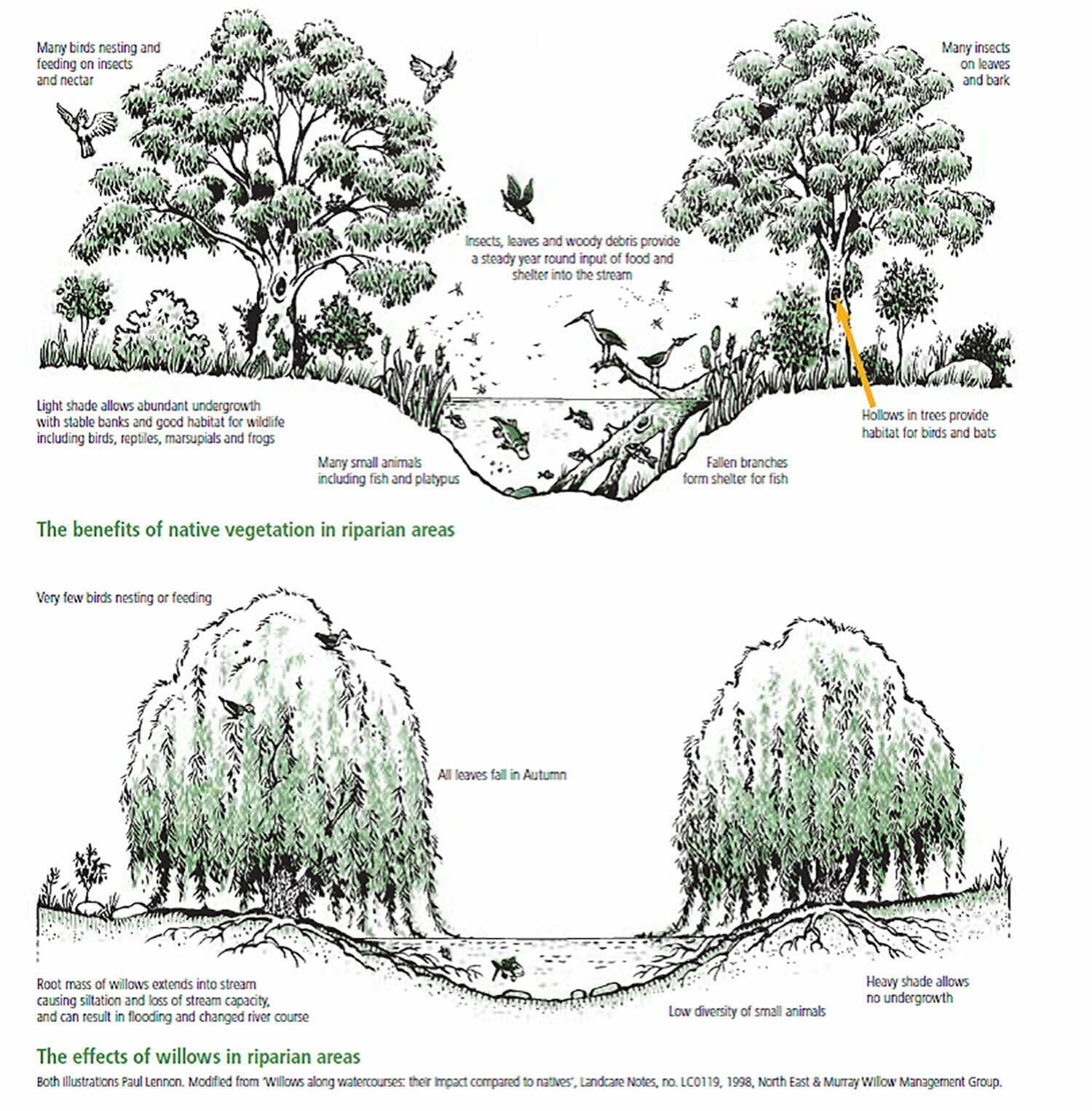

Willows reduce water quality, reducing flow and inputting large amounts of organic matter in autumn, as these deciduous trees drop soft, rapidly decomposing leaves into streams. Leaching of chemicals, such as cyanidins and delphinidins, into aquatic systems from decomposing willow detritus has also been shown to deter the herbivores that rely on leaves for their food (Rowell-Rahier, 1984 cited by Doody et.al. 2011). Conversely, the native riparian evergreen River Red Gum (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) and River Ribbon Gum (Eucalyptus viminalis) lose hard, slowly decomposing sclerophyll leaves year-round, as an adaptation to regulate evaporative losses. A diverse range of native macroinvertebrates are adapted to breaking down native vegetation in different ways, providing important inputs into the food chain. This diversity is severely restricted in systems where only willows are present.

Large spreading willow canopies create significant shading when located within water bodies, reducing the amount of sunlight reaching the stream, potentially altering stream temperature and primary production. Willows also inhibit growth of understory species and biodiversity along colonized river reaches which reduces biodiversity of wildlife that a river or stream can support. The thick willow roots also colonise instream habitat which would otherwise be used for frogs, macro invertebrates and fish spawning.

In contrast, native gums create less shade, possessing open, sparse canopies, that support diverse understory terrestrial plants and macrophytes. On the plus side, however, it must be noted that willows are better than no vegetation at all, as their presence provides a level of bank stabilization depending on their location in-stream, and vegetation provides shade and fodder for livestock during drought periods. Ideally though, if we want healthy biodiverse rivers and streams, we need healthy, functioning native vegetation along our waterways as that is what our ecosystems are designed to thrive within. The diagram below shows the difference between a willow dominated and a native dominated river system.

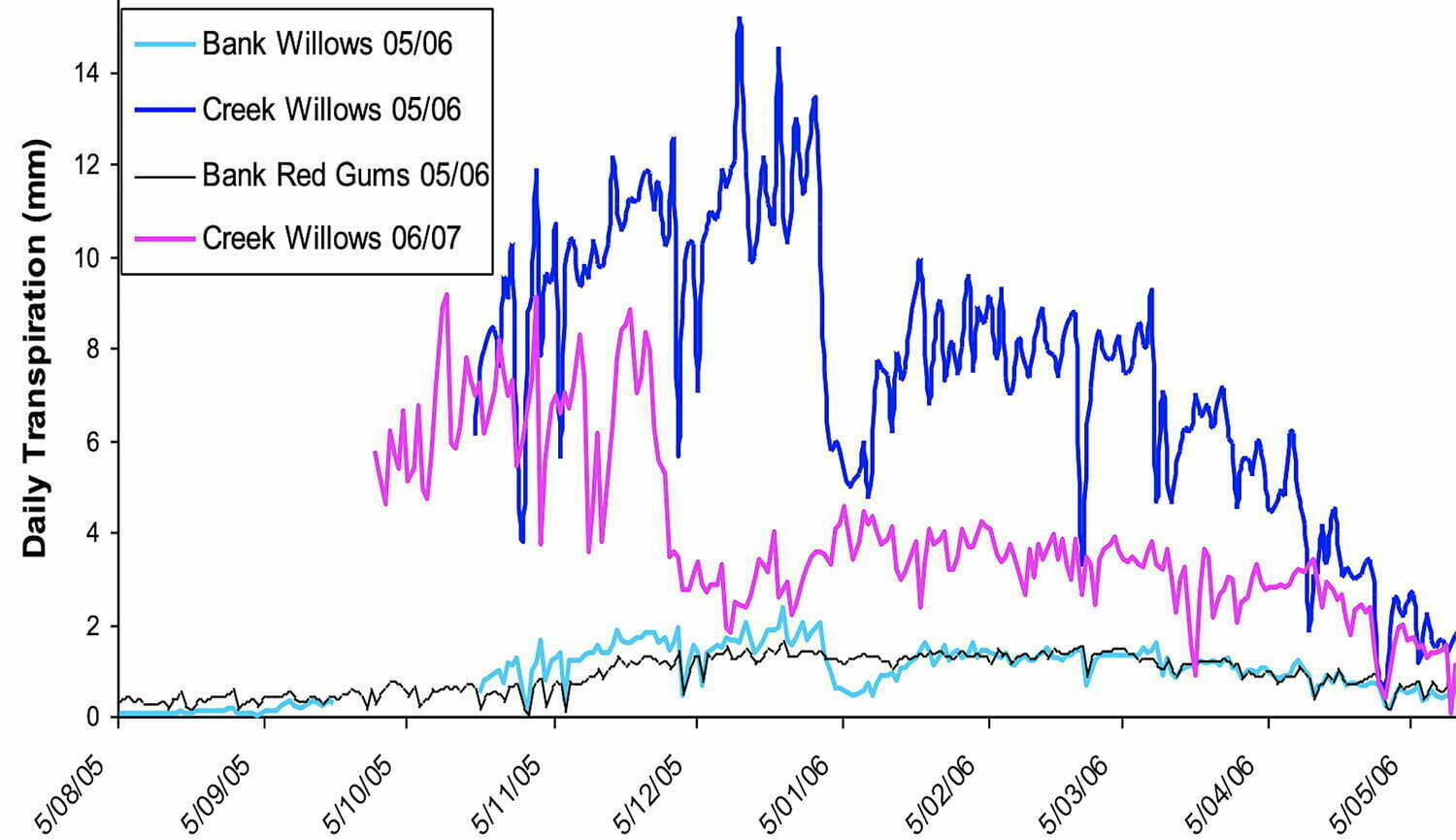

Willows use more water than native vegetation

Another important fact about willows is that they use more water than native vegetation. Research by Doody and Benyon (2010) has shown through water balance calculations over a three-year period, an average potential net water saving of 5.5 ML/year/ha of crown projected area is achievable by removal of in-stream willows with permanent access to water. On stream banks, replacement of willows with native riparian vegetation will have no net impact on site water balances. That is, willows use a lot more water than native vegetation, and this is particularly significant in ephemeral streams where surface water is reduced often to chains of ponds in dry seasons. Willows can also restrict physical access to open water for humans and other animals.

In the case of the Boorowa River in NSW, 30km of willow control was undertaken (along with fencing, revegetation and regeneration of native vegetation) above the town water supply, which returned an estimated 57ML which is one quarter of the water holding capacity of the water supply dam. These calculations were based on research undertaken by Doody and Benyon (2011), and was particularly significant during drought when water runoff was low (Gould 2013).

Willows also transpire (lose water through evaporation off leaves) at a higher rate than our native plants do, disrupting the natural water cycle and directly taking water out of rivers and into the atmosphere. The difference in transpiration rate between willows and native vegetation is illustrated in this graph found here (Doody et al.):

Comparing willow and eucalyptus transpiration.

Source: Doody, Tanya M. (2011)

Managing willows

Willow management is not straightforward. The need for willow control depends on the nature of the site, the types of willows present, the grazing regime of a site and potential future impacts that willows may have. For example, a small stream with a few Weeping Willows (Salix babylonica) dotted along in a grazed agricultural landscape is unlikely to pose any major threat to biodiversity and water quality (even if the site is fenced from stock). These trees are also likely to provide some shade and fodder for stock. A few Crack Willows (Salix fragilis), however, in the same circumstances have the potential to colonise a small stream in a relatively short space of time, particularly if ungrazed. These willows become a monoculture at the expense of biodiversity and ecological function.

Similarly, seeding Willows such as Black Willow (Salix nigra) can colonise very quickly. In this situation, it is advisable to control these using stem injected Glyphosate 360, cut and paste or overspray (if they are small enough), before they become a large infestation. This is particularly valuable if there is existing native vegetation. Note that Glyphosate 360 is the only chemical registered for use along waterways.

Cutting and painting willows.

Work in the Upper Lachlan.

Photos credit: Mary Bonet

In the case where willows have already colonised heavily, the situation is more complex. An assessment needs to be made to determine cost-benefit (as specialised machinery is generally required), likelihood of recovery of biodiversity, connectivity, potential for infestation of important downstream sites, risk assessment and the potential for neighbours to undertake complementary works. Often sites like these become the focus of greater community action and tend to be very expensive, needing grant assistance and landscape scale coordination.

Machinery for willow lopping.

Leave as much behind as possible for habitat.

Paint stump following removal.

The purpose of controlling and managing willows should be clearly defined for any project – generally, it is to improve water flow, stream access, water quality and biodiversity. A plan needs to be put in place to revegetate or to encourage regeneration of native vegetation to replace removed willows. This may take time and it is important to consider risks to soil stability and shelter while this occurs. It is always preferable to get on site advice through Landcare, Local Land Services, Council or other programs if available.

Rivers of Carbon

Willow removal is something we can often help landowners with when we agree to work with them on their site. Most of the funding grants that support our work will not, however, cover large scale willow removal so our options are sometimes limited. The really important thing to remember is that removing willows is just the start of the management process. Once they are gone, regular checking and pulling out or poisoning of new growth is essential.

Related story:

Taking out willows leaves more water for fish

Useful series of publications:

The River and Riparian Land Management Technical Guideline (series)

Further information:

Australian Government Willow (salix) weed management guide.

State and Territory Weed Management Guides – these guides complement Commonwealth agency recommendations but may have additional requirements or declare more weeds at a State or Territory level.

Weeds of National Significance Guides

New South Wales WeedWise – Willows

Doody, Tanya and Benyon, Richard (2010). Quantifying water savings from willow removal in Australian streams, Journal of Environmental Management pp1-10.

Doody, Tanya M., etal (2011). Potential for water salvage by removal of non-native woody vegetation from dryland river systems. Hydrological Processes. 25, pp4117–4131. Published online 14 December 2011 in Wiley Online Library

Cremer, K. etal. Riparian Technical Update 6: Controlling willows along Australian Rivers, Land & Water Australia.

Gould, Lori (2013). Boorowa River Recovery Evaluation, Masters Final Report, Canberra

Willow Impacts on Australian Water Resources

Doody, Tanya M., etal (2011). Potential for water salvage by removal of non-native woody vegetation from dryland river systems. Hydrological Processes. 25, pp4117–4131. Published online 14 December 2011 in Wiley Online Library