Citizen science, the involvement of volunteers from the general community in academic research, has become increasingly important in conservation science. Aided by the internet, the popularity and scope of citizen science appears almost limitless. For citizens, the motivation is to contribute to science and better conservation outcomes. For researchers, citizen science provides an opportunity to gather information that would be impossible to collect because of limited resources.

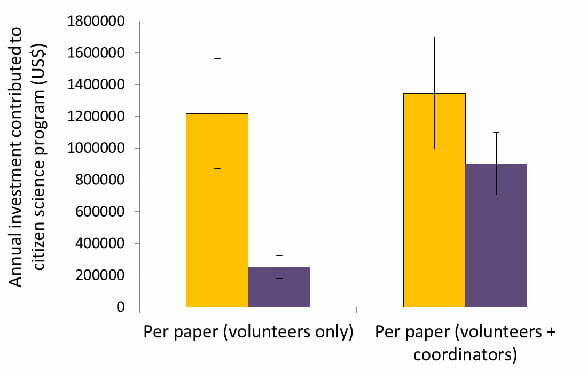

So, how much of a contribution is citizen science actually making? We recently reviewed scientific publications applying citizen-science bird-monitoring programs to determine their influence in the scientific literature, and whether or not they are useful for informing management decisions (Tulloch et al, 2013). Our review revealed two key things. First, there is a massive in-kind contribution in terms of survey investment by volunteers, an investment that is unlikely to be possible in most scientific projects (Figure 1). Second, the way in which a citizen science program is designed and delivered is key to whether it can inform conservation and management decisions.

Figure 1. Mean (SE) annual investment by volunteers and with coordinators added relative to publication output, in cross-sectional (orange bars) and longitudinal (dark bars) programs. This kind of investment is impossible for the majority of scientific research papers.

Real benefits

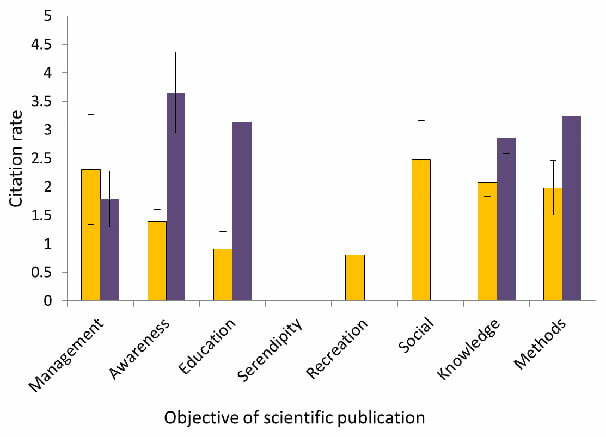

Although there has been criticism in the past about the ability of citizen science to deliver real conservation benefits, we showed that not only are multiple types of citizen science protocols useful for informing decisions, but also that they have a range of side benefits that most scientific monitoring programs fail to achieve. These benefits include increasing public awareness of conservation, education, recreation, social and economic research, and learning to improve methods of monitoring and evaluation (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The impact (in terms of number of times cited per year) of different kinds of citizen science programs relative to the objective for which they were used in scientific publications (orange = crosssectional schemes such as Atlases – collections of surveys of many species contributed by volunteers over a set period of time; purple = longitudinal schemes such as Breeding Bird Surveys (BBS) – on-going stratified monitoring of sites that require more coordination).

The most-frequent application of citizen-science research was to improve ecological knowledge – learning for learning’s sake – this knowledge informs management decisions that require an underlying understanding of how species respond to different environmental conditions, or why species occur in one location and not another.

As we struggle to address all of the threats affecting our declining biodiversity, particularly in sparsely populated and difficult-to-access places like Australia, citizen science will become the only practical way to achieve the geographic extent required to document ecological patterns and address ecological questions at scales relevant to species range shifts, migration patterns, disease spread, broad-scale population trends, changes in national and state policy, and impacts of environmental processes like climate change.

There is a massive in-kind contribution in terms of survey investment by volunteers, an investment that is unlikely to be possible in most scientific projects.

Tracking invasion

In our review, the study with the highest influence on the scientific literature (a whopping 21.5 citations per year on average) investigated the emergence and impacts on birds of the deadly West Nile Virus in the US (LaDeau et al, 2007). Citizen scientists are the perfect tool for tracking and perhaps even managing the spread of invasive species and diseases, with a recent application in the UK for tracking the invasive grey squirrel and informing where to manage the invasion front. With attention in Australia focused on how native species and invasive species such as cane toads might spread under future changed climate conditions, citizen scientists are primed to play an increasing role in managing their spread before it is too late.

Of course, gaining knowledge about management usually requires ancillary information about that management (eg, grazing or fire or logging). This is rarely a part of citizen science, so the future success of citizen-science programs hinges on good collaboration with organisations collecting landscape-level data that might be combined with the huge monitoring efforts of citizen scientists.

Making the most of citizen science

To ensure citizen science data are used to their full potential, we recommend the following:

- That we learn: Elements of successful citizen science protocols are incorporated into future programs, emphasising: (a) fine-scale data collection, (b) temporal replication that covers the full range of habitats or land use types, and (c) communication of data needs with volunteers.

- That we maintain quality: Regional coordinators are in place to maintain data quality.

- That we communicate: Communication between researchers and the organisations coordinating volunteer monitoring is enhanced, with monitoring targeted to meet specific needs and objectives.

- That we seek to fill the gaps: Application of citizen science programs to under-explored objectives and species is encouraged, and data are made freely and easily accessible.

One exciting example of successful communication and a growing citizen-science network is the Australian program Fungimap, which encourages citizens to report and send in photos of some 220 target species. This effort led to one of the first ever fungi ID guides in the world.

But it’s not just bird lovers (or even fungi lovers) who will be contributing to this new movement. With the emergence of new technologies, greater networking and the rise of open-access science, citizens of all types will have the capacity to participate in citizen science and play a role in monitoring and managing biodiversity into the future. A more formalized citizen-science enterprise, complete with networked organizations, associations, journals and cyber-infrastructure, will advance research and further educate the public.

This is already becoming possible with programs such as eBird (see Birding into the 21st Century), the Atlas of Living Australia’s Citizen Science portal and recent formation of the Australian Citizen Science Association (see our story on the ACSA).

More info: Ayesha Tulloch ayesha.tulloch@anu.edu.au

References

LaDeau SL, AM Kilpatrick & PP Marra (2007). West Nile virus emergence and large-scale declines of North American bird populations. Nature 447: 710–713.

Tulloch AIT & JK Szabo (2012). A behavioural ecology approach to understand volunteer surveying for citizen science datasets. Emu 112: 313-325.

Tulloch AIT, LN Joseph, JK Szabo, TG Martin & HP Possingham (2013). Realising the full potential of citizen science monitoring programs. Biological Conservation 165: 128-138.

This post is copied with permission from Decision Point Online, edited by David Salt for the Environmental Decision Group – the direct page link is here.

Banner Image: Flickr. (2019). Red-tailed Black Cockatoo (Calyptorhynchus banksii). [online] Available at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/9919745@N03/8603115638