Carbon sequestration is the process of removing and storing atmospheric carbon dioxide in carbon sinks such as forests, mangroves and agricultural soils.[1] Reforestation, involving the re-establishment of woody vegetation on previously cleared land, is widely recognised as an effective tool for sequestering carbon. Reforestation involves either changing current land management to increase the cover of woody vegetation, or actively establishing new plantings through sowing seeds or planting tube-stock seedlings.

In Australia, promoting reforestation accounts for approximately 58% [2] of all carbon credits contracted under the Carbon Solutions Fund (see Box 1). The majority of these credits fall under the ‘Human-Induced Regeneration of native forests’ [3] methodology, and occur predominantly in the semi-arid Mulga woodlands of south-west Queensland and North-West New South Wales. At the global scale, the future sequestration potential from reforestation has been estimated to be, over the next 30 years,[4] on average 5.9 – 8.9 Gt CO2-e yr-1, or approximately 15 – 22% of current annual human-induced emissions. To limit the worst effects of climate change, it has been estimated that human emissions must reach net zero by 2050,[5] to be achieved by a combination of direct emissions reductions, and sequestration. To give an idea of the magnitude of these numbers, 1Gt of CO2-e is approximately equal to the mass of water in two Sydney harbours.

The Climate Solutions Fund is one component of the Australian Government’s Climate Solutions Package, designed to ensure Australia meets its international commitments to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 under the Paris Accord. The program seeks to reduce emissions across the economy through funding activities (‘projects’) that reduce emissions and/or sequester carbon, whilst at the same time providing farmers, small businesses and Indigenous communities the opportunity to improve the local environment and benefit from new revenue streams. The fund covers multiple sectors and supports practical projects in vegetation management, agriculture, manufacturing, energy, mining, oil and gas, transport, waste and wastewater. Read more about the Climate Solutions Fund.

Whilst carbon sequestration by vegetation is an important tool for helping to offset human-induced greenhouse gas emissions, it is only one of a number of valuable ecosystem services that reforestation activities provide. Indeed, for many landholders the carbon sequestered may be secondary to a whole host of other benefits.[6] These include:

Environmental benefits such as new habitat to support biodiversity, improved soil nutrition and stability, and increased soil water storage and reduced erosion.

Social, such as providing amenity and recreation opportunities that enhance aesthetics and well-being, and

Economic benefits such as wood products, crop pollination services, buffering crops and grazing pastures from extreme wind, heat and frost, as well as providing shelter for stock.

Block or belt plantings?

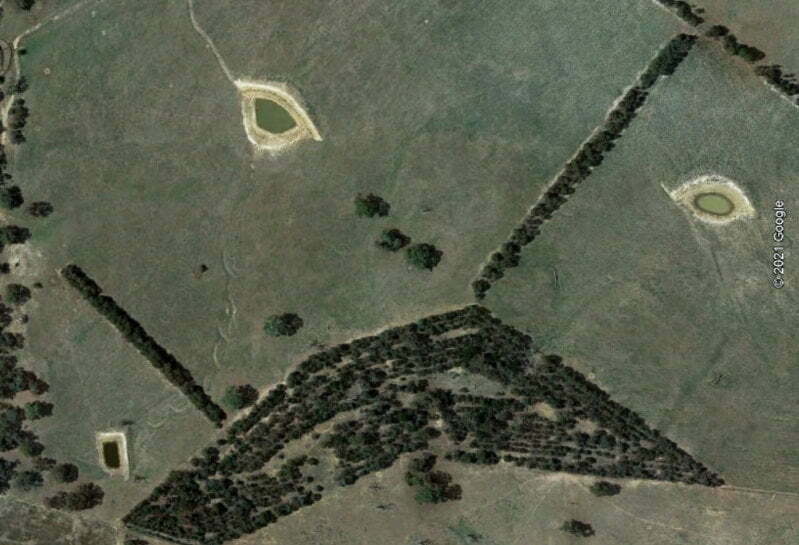

The spatial layout of reforestation plantings has a direct bearing on the range and quality of additional benefits provided. Broadly speaking, new plantings are either established in large ‘blocks’ at the scale of whole paddocks or more, or in narrow ‘belts’ that range from a few metres wide to a few 10s of metres wide, and that are often planted in narrow strips along the edges of existing paddocks. The species mix is also important, with ‘environmental plantings’ of mixed native species typically sequestering less carbon than monoculture plantings of commercial species; but providing greater biodiversity outcomes.[7]

Whilst block plantings provide the greatest sequestration opportunity, it is belt plantings that are currently receiving significant interest.[8] This is because belt plantings can be more readily integrated into existing farming practices, with the potential to improve overall farm economics and environmental outcomes. For example, case studies in Tasmania have demonstrated a mixture of farm forestry and agriculture can yield higher economic returns than either trees or agriculture alone.[9] This occurs through both an income supply stream from wood products from the plantings, but also enhanced pasture production arising from reduced windspeed and subsequent reduced evaporation in adjacent pastures, leading to greater overall productivity.

Belt plantings and riparian zones

Belt plantings are also most appropriate for the restoration of riparian vegetation, as it runs alongside the river or stream, or around the edges of wetlands and swamps. In addition, we know that riparian vegetation provides a host of other benefits such as stream bank stabilisation, reduced rates of runoff, decreased sedimentation loads, habitat for wildlife, and shade and shelter for stock. To date, little has been done to focus on belt plantings in the riparian zone to produce carbon sequestration benefits.

Recent work, however, shows significantly higher rates of growth in riparian vegetation as riverbanks have deeper soils and vegetation can access groundwater unavailable to adjacent non-riparian rain-fed only systems.[10][11] Landowners already working to fence off, protect and regenerate their riparian zones will therefore also be sequestering carbon in these areas at higher rates than elsewhere on their property. This suggests widespread riparian restoration could simultaneously provide enhanced carbon sequestration benefits, whilst at the same time contributing significantly to improved stream health and water quality outcomes. The opportunity is there; the challenge lies in making it happen.

Dr Stephen Roxburgh is a recognised leader in terrestrial plant ecology and greenhouse gas accounting, with over 20 years experience in the field measurement and computer modelling of forest growth and carbon cycling. He joined CSIRO in 2008 where he leads a team of researchers investigating forest growth, carbon sequestration, and the implications of climate change on forest productivity. Stephen works closely with the Australian government to develop robust methods for greenhouse gas accounting, including impacts of wildfires, the carbon sequestration of forest revegetation, avoided deforestation, and the carbon balance of harvested native forests.

References

- ^ https://www.environment.sa.gov.au/topics/land-management/sustainable-soil-land-management/carbon-sequestration

- ^ www.cleanenergyregulator.gov.au/Infohub/Media-Centre/Pages/Resources/ERF%20media%20resources/12th-Emissions-Reduction-Fund-Auction-infographics.aspx

- ^ https://www.industry.gov.au/regulations-and-standards/methods-for-the-emissions-reduction-fund/human-induced-regeneration-of-a-permanent-even-aged-native-forest-11-method

- ^ Cook-Patton S. C. et al. 2020. Mapping carbon accumulation potential from global natural forest regrowth. Nature 585, 545-50.

- ^ https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/2/2019/02/SR15_Chapter2_Low_Res.pdf

- ^ Fleming A., Stitzlein C., Jakku E. & Fielke S. (2019) Missed opportunity? Framing actions around co-benefits for carbon mitigation in Australian agriculture. Land Use Policy 85, 230-8.

- ^ Paul K. I., Cunningham S., England J., Roxburgh S. H., Preece N., Brooksbank K., Crawford D. & Polglase P. (2016) Managing reforestation to sequester carbon, increase biodiversity potential and minimize loss of agricultural land. Land Use Policy 51, 135-49.

- ^ https://www.climatechangeauthority.gov.au/publications/reaping-rewards-research-report

- ^ https://www.fwpa.com.au/rdworks-newsletters/2064-forestry-and-farming-unite-for-everyone-s-benefit.html

- ^ Paul K. I. & Roxburgh S. H. (2020) Predicting carbon sequestration of woody biomass following land restoration. Forest Ecology and Management 460, 117838

- ^ https://nesptropical.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/NESP-TWQ-Project-3.1.4-Final-Report.pdf

Our Carbon Science Resources

We are fortunate to have researchers in Australia who are keen to make their science applicable in the ‘real world’ and meaningful to our landholders. Rivers of Carbon is continually embracing new knowledge, whether that be from science or experience, so that we can provide the best advice and gain optimum environmental and social outcomes.